While we need to set high standards for sustainability in apparel production, are we too woke-washed to realise we mostly offer criticism, but not much else?

By now, everyone in fashion has heard about the class action lawsuit filed in the Southern District of New York in July 2022 that accused H&M of deceiving consumers about the veracity of its sustainability claims through the use of “false and misleading” environmental scorecards and advertising.

This came about at the back of the recent Higg Index ‘sustainability scorecard’ controversy, where Norwegian outdoor wear brand Norrøna was asked by the Norwegian Consumer Authority (NCA) to pull down their use of the ‘Sustainability Scorecards’ on their website and corresponding materials.

H&M’s class action lawsuit was in relation to both the use of the Higg Index Sustainability Scorecards, and greenwashed ‘misrepresentations’ generally, where it claims its products are ‘conscious’, a ‘conscious choice’, made from ‘sustainable materials’ and prevented, through its recycling program, ‘from going to the landfill’ through the use of green hang tags, in-store signage and online marketing.

We know a crackdown on greenwashing is absolutely needed in fashion and apparel, as there are currently varying degrees of minimum criteria when it comes to defining a product line ‘sustainable’ in fashion and apparel. Even though these recent developments have been welcomed by consumers and industry watchdogs alike, I think the precedent set by the consumer watchdogs in both the USA and Norway can have ripple effects in terms of its potential for driving change in this sector, and if I may, I’d like to offer a critique on the repercussions from a different lens.

Before I go further into this, let’s recap on a number of key elements of the Higg controversy that require breaking down past sensationalised news headlines we’ve been littered with in the spirit of these developments since June 2022.

What is the Higg Index?

The Higg Index is a widely used suite of tools created for the fashion industry to assess the sustainability of the materials used in their products. It was created in 2011 by a group of industry heavyweights, including H&M, Walmart, Nike, Levi’s, and Patagonia. It is maintained by the Sustainable Apparel Coalition (SAC) and their technology partner Higg. The SAC has about 250 member brands.

The Higg MSI – Materials Sustainability Index – in particular, is a tool that calculates environmental impacts of over 90+ materials often used in apparel and textiles, using data submitted from industry and life cycle assessment (LCA) databases.

In May 2021, SAC launched its customer-facing transparency program, with an announcement that Amazon, H&M, and Norrøna among the first brands to participate. The program, at the time, planned to focus on the environmental impact of a product’s materials, and will expand over the next two years to incorporate additional data including manufacturing and corporate responsibility.

However, in June 2022, the Norwegian Consumer Authority, NCA has officially taken issue with SAC regarding the use of LCA data being used to support consumer facing environmental claims.

Why does the finding from NCA matter?

On June 16th 2022, the NCA banned the usage of the Higg Index in marketing, and issued a warning to H&M to curb its use on their website as they believed the SAC should not allow its partners to use Higg Index ‘Sustainability Scorecard’ to market to consumers. Norway believes that this sets a precedent in Europe and warns the SAC that it may face ‘economic sanctions’ if there are further violations of its Marketing Control Act. They had previously issued a similar warning to Norrøna.

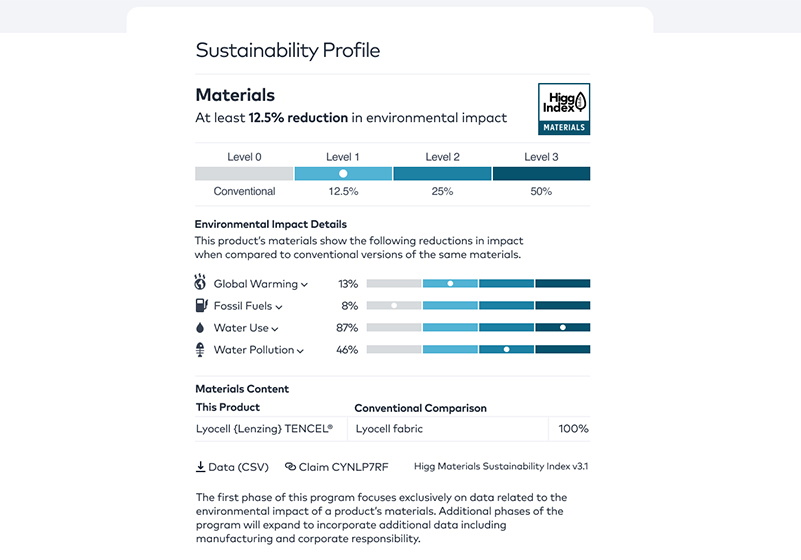

A screenshot of the Sustainability Scorecard for an item on Norrøna’s website

What are the implications from this finding?

Data from the Higgs Index is complex, and can be misleading to everyday consumers.

When Norrøna originally employed the transparency platform to tout the improved sustainability profile of some of its products, it included a visual scorecard indicating that its organic cotton T-shirts produced 14 percent fewer emissions, used 9 percent less fossil fuels, required 88 percent less water and created 47 percent less water pollution than their conventional counterparts. This, the NCA said, misled consumers because the information supplied referred to the average environmental attributes of the cotton fibre, not those of the specific finished items, meaning there was insufficient proof that the claimed impact reductions were “true and correct.”

SAC’s response

As at June 27 2022, the consumer-facing effort has been suspended. According to SAC’s media statement, “We have made the decision to pause the consumer facing transparency program globally as we work with the NCA and other consumer agencies and regulators to better understand how to substantiate product level claims with trusted and credible data. This specifically means temporarily removing the published Higg Index seal and scorecard from the participating online retail platforms while further evaluation takes place.” To this end, SAC has commissioned an independent third-party expert review of the Higg MSI data and methodology. Norrøna has also provided a response here.

What is LCA, why is it important, what makes LCAs credible?

Life cycle assessment (LCA), also known as a ‘cradle-to-grave’ or ‘cradle-to-cradle’ analysis technique, is a methodology for assessing environmental impacts associated with all the stages of the life cycle of a commercial product, process, or service. For instance, in the case of a manufactured product, environmental impacts are assessed from raw material extraction and processing (cradle), through the product’s manufacture, distribution and use, to the recycling or final disposal of the materials composing it (grave).

An LCA study involves a thorough inventory of the energy and materials that are required across the industry value chain of the product, process or service, and calculates the corresponding emissions to the environment. LCA thus assesses cumulative potential environmental impacts. The aim is to document and improve the overall environmental profile of the product.

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and their procedures in particular, ISO 14040: Environmental management – Life cycle assessment – Principles and framework and ISO14044: Environmental management – Life cycle assessment – Requirements and guidelines is the widely recognised standards for conducting LCAs. ISO 14025: Environmental labels and declarations – Type III environmental declarations – Principles and procedures, also relies heavily on independent, verifiable LCAs.

The most important applications of LCAs are: 1) the analysis of the contribution of the life cycle stages to the overall environmental load, usually with the aim to prioritise improvements on products or processes, and 2) comparison between products for internal use.

Criticisms have been leveled against the LCA approach, both in general and with regard to specific cases (e.g. in the consistency of the methodology, particularly with regard to system boundaries, and the susceptibility of particular LCAs to practitioner bias with regard to the decisions that they seek to inform). In turn, an LCA completed by 10 different parties could yield 10 different results, even with the ISO 14040 and ISO 14044 methodologies applied.

Example of Life Cycle Analysis system boundary

Are we too critical that we unknowingly contribute in ‘cancel culture?’

I think greenwashing is prevalent in a lot of forms, and the Higg ‘Sustainability Scorecard’ could definitely be taken as greenwashing. However, any effort to shut down a highly utilised and trusted industry tool needs to be constructive. The Higg Index acts as a starting point for the industry rather than an end game solution. There’s bound to be issues such as insufficient data considering that this industry has a complex supply chain. SAC has stated numerous times that collaboration is important to fill in the data gaps.

For someone who works in the industry and has used Higg’s suite of tools, you can’t help but feel ‘attacked’ when outsiders who may not appreciate the effort and work that has gone into developing these metrics and calculations are shut down so swiftly, and more so by those who perhaps don’t understand the intricacies behind LCAs, eco-footprinting, aggregating research data, embodied emissions in materials, and the concept of environmental product declarations.

I personally think the Higg Index is a great resource. The data (as sustainability practitioners understand it) needs refining and will be refined over time. Can you introduce me to anybody who works in this field who doesn’t agree? While constructive criticism is important, the index should not be slammed but rather given further feedback to improve over time, and to have their data be reviewed by external sources to ensure its accuracy and transparency. I think the creation of SAC itself is a big milestone for fashion brands, in the spirit of working together and sharing competitive information, something the industry is notorious for not doing.

To quote a heart-warming story of how SAC came to be, many years ago, the original group of pioneers in this space decided that if they don’t start somewhere, they will never make a ‘standard’ lift off the ground. One of the principles the group was guided by was, ‘don’t let perfect get in the way of good enough’.

The Higg controversy narrative conveniently forgets about the concept of sustainable development

LCA information availabilities for products, process and services are not limited to apparel and footwear. Construction products that contribute to the built environment, housing, and public infrastructure also face similar issues.

Take rating tools and schemes that exist out there to incorporate not only transparency but performance-based metrics for built environment, such as BREEAM (UK), Greenstar (AUS), and Envision (USA). The construction industry, instead of plotting against each other in a battle of ‘who has the best tool’ out there, gets on with the job that matches their setting because it is their responsibility and their responsibility only to design our buildings and infrastructure to account for our future. (Just a tip, for a summary of built environment ratings and certifications around the world, check this out: https://fidic.org/node/5943). And whoever said that their tool is perfect?

What is missing from the Higg Index controversy reporting is the big-picture thinking needed in this industry to harmonise their sustainability agenda. Having worked in environmental and social governance for the last 18 years, one thing that stood out for me in fashion and apparel is the glaring problem of accessibility to sustainability competency by region. It seems the ‘solutions’ that are making the most noises are those that feature ‘brand’ involvement, especially global conglomerates, but also from an English-speaking point-of-view.

There are many players that make up awareness, competency and advocacy for change in the fashion supply change, and manufacturers – literally the players who hold the key to bottom-up innovations – are rarely mentioned in mainstream media on their successes and achievements to exemplify progress in this area.

Why is it always the brands, or seem to be the brands, who are supposedly the only ones spearheading change?

Moreover, the Higg Index and their suite of products is – on a scale of transparency – more complete than any other effort other brands or coalitions can emulate. Think about the collective data sharing and collaboration that is happening in Southeast Asia, for example. There isn’t any. Are we dissuading progress for other regions responsible for the production of apparel and footwear? Should we be letting perfect get in the way of good enough?

My personal take on it is that data collection for materials in the fashion and apparel supply chain should be driven by each country producing it, because harmonisation of materials comes from none other than where they are produced. The systemic monitoring, progress of reporting, and troubleshooting should happen at this level, overseen by a textile and apparel industry association in each region.

The other missing link in the recent reporting of the controversy is how the many ratings and tools for certifications in areas in the fashion and apparel supply chain can be harmonised from a sustainable development point of view. Sometimes it’s easier to say fast fashion needs to stop, but the reality is we will produce clothes for people to wear and textiles to furnish our homes, no matter the time, year, or day, and especially to satiate demand from emerging markets.

Hence the concept of sustainable development. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) already provides a blueprint for how we consider all aspects of development that ties so many impact areas together, no matter for everyday people, organisations, businesses, and governments. Its language is universally accepted and can be measured across all levels. Is fashion and apparel solely interested in how their products ‘appear’ to be a more responsible choice for humanity, or does the industry want go that one step further to be united in its front to tackle humanity’s biggest challenges?

An ‘eco-label’ can’t be such a bad thing, can it?

It’s hard enough for consumers to understand sustainability information as they are being presented now, and this sort of headline is definitely not consumer-friendly. The Higg Index controversy risks slowing the ability of consumers to use sustainability information in their purchasing decisions.

I have always been of the view that an easy-to-comprehend sustainability scorecard is something that will sway consumers to be more responsible purchasers. In 2016, I founded FASHINFIDELITY, an online platform that solely exists to deconstruct complex supply chain information and news stories, much like this one. Polls with our followers suggest an overwhelmingly high interest in a universally accepted clothing ‘footprint’ labelling.

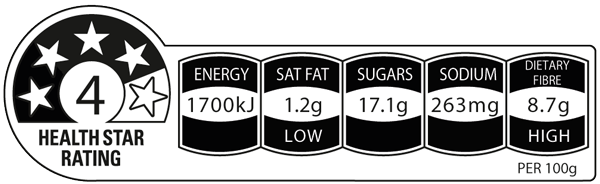

We know currently there is work by Peter Gorse, Textile Researcher at Cranfield University on a ‘Garment label’ akin to our food’s Nutritional label that has gotten a lot of traction by consumers and brands alike.

“Garment Facts” label prototype by Peter Grose (do not reproduce without prior permission)

Sourcing Journal recently published an article that purports that out of a sample of consumers, when asked what they really want to see on an ‘Eco-Label’ for garments, the main concern was recyclability at 45%, followed by human rights for 39% of respondents. Chemical use, animal welfare and material use were each deemed a priority by 33% of consumers, quoting a study conducted by Responsible Business Coalition.

The implications from the H&M lawsuit and the Higg Sustainability Scorecards have wide repercussions. If brands decide to use Gorse’s ‘Garment Facts’ label, could he be sued, too?

The bigger picture of responsible consumer marketing

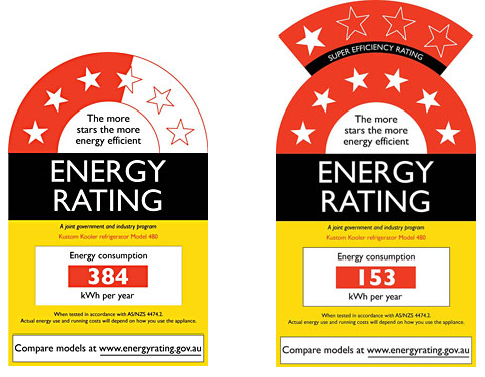

In Australia where I live, we have a health rating tool on food products in supermarket shelves, that gives you a figure of 1 to 5 stars to indicate its ‘health’. We are also used to metrics such as the Energy Rating on whitegoods such as kitchen appliance, or the Water Efficiency Labelling Standard.

I can’t recall a time where food brands or appliance companies sued the government as ‘misleading’ the consumer.

With all the talk of transparency to move the needle for more responsible and ethical production of apparel and textiles, as consumers we have just had enough. We deserve better, and we want standardised, reputable garment eco-footprinting, now. Fashion and apparel should just get on with placing product labels, pronto. If it means it is the Higg Sustainability Scorecard, so be it. To do this though, intellectual property issues need to be sorted out to ensure accessibility and coverage for all brands, big or small. The exorbitant prices that SAC charges should be levelled out so anyone and everyone can partake in driving the transparency and performance agenda.

The more consumers are used to ‘ratings’ being made visible at point of purchase, the more we normalise the power of consumers’ purchasing decisions, and before you know it, it’s just another part of choices everyone needs to consider, that makes up our everyday purchasing decisions.

Join us in our Slow Fashion movement with the hashtags #ConscientiousFashionista and #wardrobetruths on Instagram, and follow us at @fashinfidelity.

Tags: #greenwashing #lawsuit #consumerlaw

#norrona #hm #higgindex #higg #conscientiousfashionista #fastfashion #slowfashion #wardrobetruths #fashioneducation #fashion #fashinfidelity

conscientiousfashionista, consumerlaw, eco-friendly, ethical fashion, fashion, fashioneducation, fastfashion, greenwashing, higg, higgindex, hm, lawsuit, norrona, slowfashion, sustainability, sustainable fashion, wardrobetruths